Science as an inefficient process

Hull, Hofstadter, and justifying research to a skeptical public

At the start of the year I finished two books that had dogged me for months. Though I was glad to leave them behind, both have stuck with me, as anyone who has gone for a run with me recently knows. To break a long silence—and because they are helping me make sense of the current moment—I thought I would write about them here.

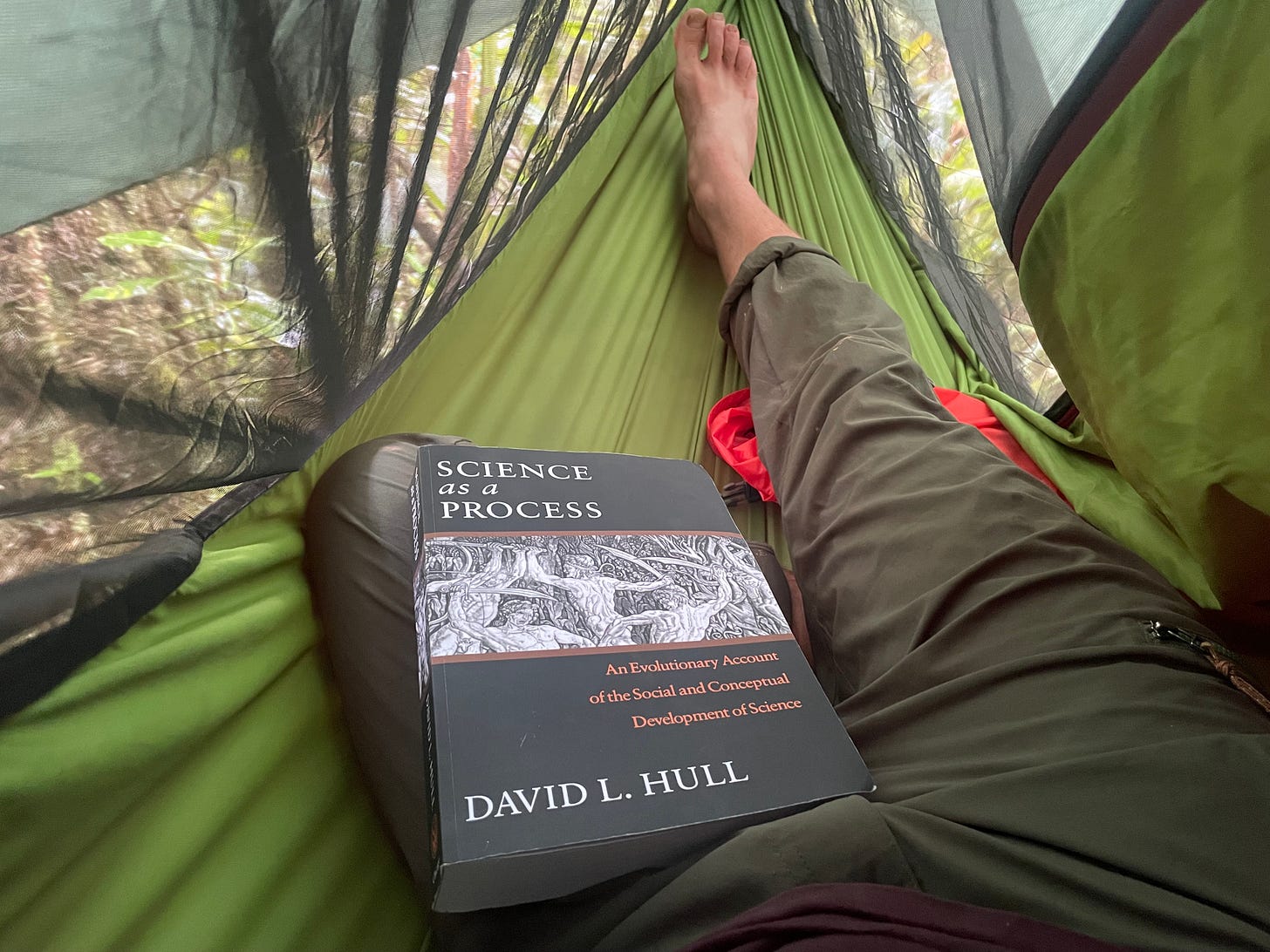

I started the first, David Hull’s Science as a Process, during a segmented and chaotic trip from Bozeman to Albuquerque through Silverton and Santa Fe. At the Sunport I boarded the first of many flights to Kimbe, Papua New Guinea, where, grad student in tow, I visited government offices, endured languid days at the Liamo Reef Resort, and eventually spent the better part of two weeks in the field with nothing but Hull and a field guide to pass the evenings. (More on that later, maybe.)

The half of Science as a Process I managed to read by headlamp from my hammock is an exhaustive (exhausting) account of the so-called ‘Systematics Wars’ of the 1970s and 80s, a series of academic bar fights over the methods and philosophy underpinning taxonomy. If this conflict is obscure to you, you are in good company; if it is not, you may be kind of person who would search eBay for a ‘Willi Hennig Superstar” t-shirt.

I reluctantly fall in the latter camp, having learned of the episode during grad school while taking a course on phylogenetics from Joe Felsenstein. Felsenstein, as important to modern phylogenetics as anyone, was somewhere between a neutral observer and participant in the Systematics Wars, and had endless entertaining digressions for us about its central issues and characters, some of whom would resurface in the news the following year. With background in the material and skin in the game I found Hull’s play-by-play interesting enough; I can’t say I would recommend it to many.

The back half of Science as a Process is less well-known and more thought-provoking. Hull, a historian and philosopher of science, argues that science advances via a ‘selection process’, or a progressive winnowing of ideas analogous to the evolution of organisms by natural selection. In this framework, scientific concepts either become widespread or fail to catch on due to interactions among individual scientists and the research groups they form. Scientists are curious, want credit, and cooperate with each other to strategically advance their work and the work of their allies. Though these motivations are independent of the merit of their ideas, merit is not irrelevant: Good ideas float to the top, Hull suggests, because the social structure of science incentivizes their adoption and relatively good behavior on the part of scientists.

When Science as a Process was first published in 1990, its central thesis was far from universally embraced. Today, after two decades of a replication crisis, a collapsing academy, and high-profile cases of outright fraud, his optimism can seem misplaced. But I nonetheless found many of Hull’s points still ring true. Though scientists endlessly admonish each other to maintain objectivity, science works despite its participants' blind spots, as the biases of competitors are typically self-correcting. And though we ring our hands about the ever-growing bolus of unread, shoddy papers, this waste might be as unavoidable an aspect of the system as harmful, quickly purged mutations are to an evolving population of lizards. Science, as Hull describes it, is messy, human, inefficient—and very effective.

I started the second book on my stack, Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, the week following November’s presidential election. Reading this 1964 Pulitzer Prize Winner in 2025 can be startling: 1950s America, it turns out, was not such a different place, from rampant anti-vaccine sentiment to a fear of fluoridated water. Hofstadter traces the long history of skepticism and outright hostility to intellectualism in the US from revival meetings in Puritan New England through the McCarthy era to Sputnik. In doing so, he paints a picture of a nation whose desire to buck patrician European snobbishness led it to produce the greatest university system in the world—and a perpetually alienated intellectual class.

At some level I found the book’s long view reassuring: Today’s reactionary attitude towards higher education and expertise is neither new nor foreign, a cyclical manifestation of distrust that is as likely to wane as it is to wax. Yet its central paradox is more disquieting. It would seem that some of America’s best and most distinctive qualities—individualism, practicality, democracy and egalitarianism—are responsible for both building our towering scientific infrastructure and seeding perennial skepticism as to its value. As in Hull’s vision of science, things that are features can also be bugs.

You might see why I am writing this now. Anyone employed at a university or as a government scientist has probably had one of the most difficult months of their career, with funding freezes, proposed budget cuts, and workforce reductions. The work of scientists in fields like systematics is only possible because taxpayers have decided it is worthwhile. For the moment, their proxies—elected officials—have decided it is not. In part, DOGE’s assault on research bureaucracy has been so effective because no one would ever claim to be pro-waste, pro-bias, pro-elitism, or pro-inefficiency. The wicked problem is how to defend our work in general terms even if these criticisms are true.

Science is rigor, or a process of rigor, but not any specific process of rigor, however closely they must resemble one another.